Drawing things together

caption

A person does comics journalism in this photo illustration.How creators of comics journalism harness subjectivity to convey truth

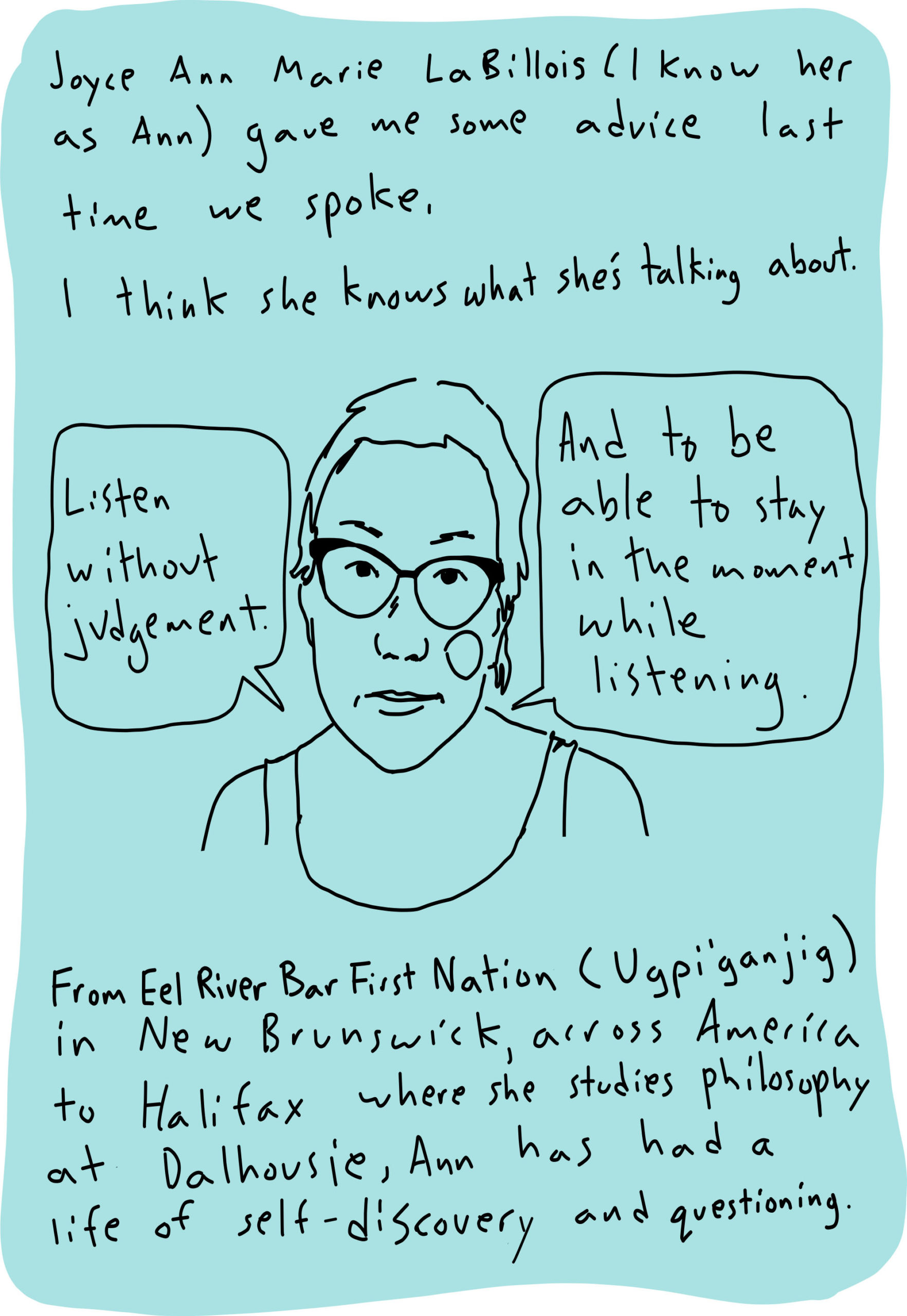

When Ann LaBillois first saw the comic, she remembers thinking, “This is me.”

LaBillois saw snippets of her recurring dreams, childhood memories and philosophical questions. Her words, written in someone else’s hand, covered the pages like her own writing – bubbling over in line-resisting shapes. Everything was laid out in 20 digital panels and web-published by one of Canada’s largest news organizations.

“It was like a part of me. Just the way he wrote it, just the visual effect of it. It felt good.”

When Jon Claytor, an artist and LaBillois’s friend, asked to interview her and make a comic about it for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), LaBillois was unsure.

She, like many, had only associated comics with fictional characters. This changed when Claytor shared a comic he drew. It illustrated a story LaBillois told about the flock of birds that passed her home every day. She was touched.

LaBillois says the bird comic and her friendship with Claytor were part of what led her to agree to the interview.

caption

A panel from Jon Claytor’s Life Paths comic, “Life of deep questions and dreams led Mi’kmaw woman to study philosophy”. Contributed by the CBC.The CBC has web-published several of Claytor’s non-fiction comics, including the one about LaBillois.

With increasing awareness about how comics can tell true stories, a genre called comics journalism is finding its way into the larger media landscape.

Comics journalism and the media world

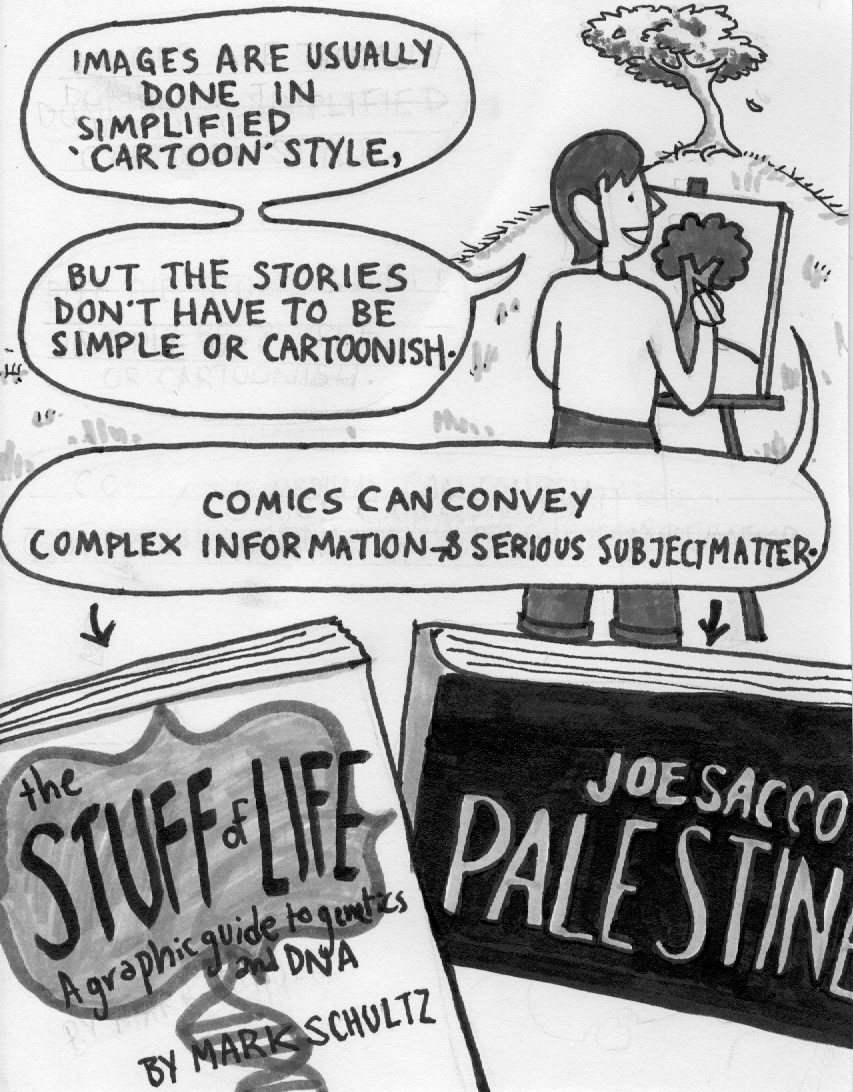

In 2016, the New York Times published a non-fiction comic series about death-row prisoners and, in 2018, it won a Pulitzer Prize for a non-fiction comic series about Syrian refugees. In recent decades, non-fiction comics publications, like Symbolia and The Nib, have developed online, and non-fiction comic books have detailed news events such as Hurricane Katrina and the war in Bosnia.

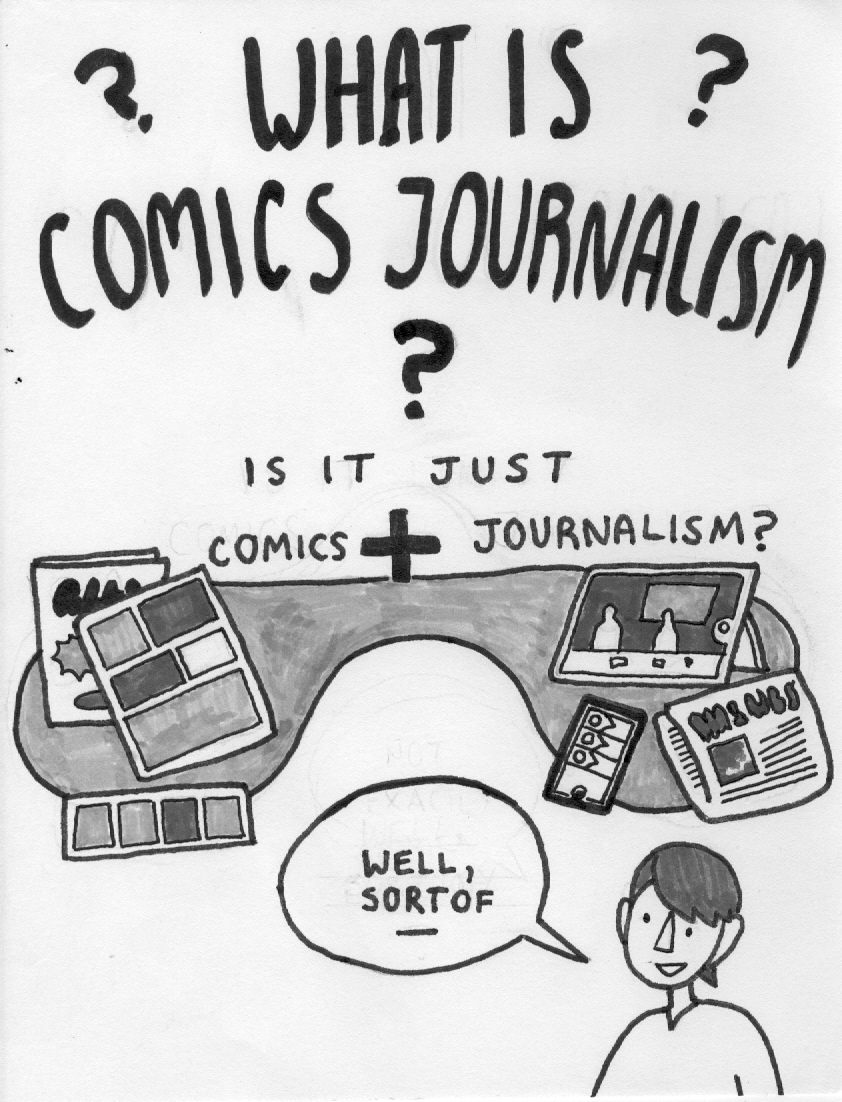

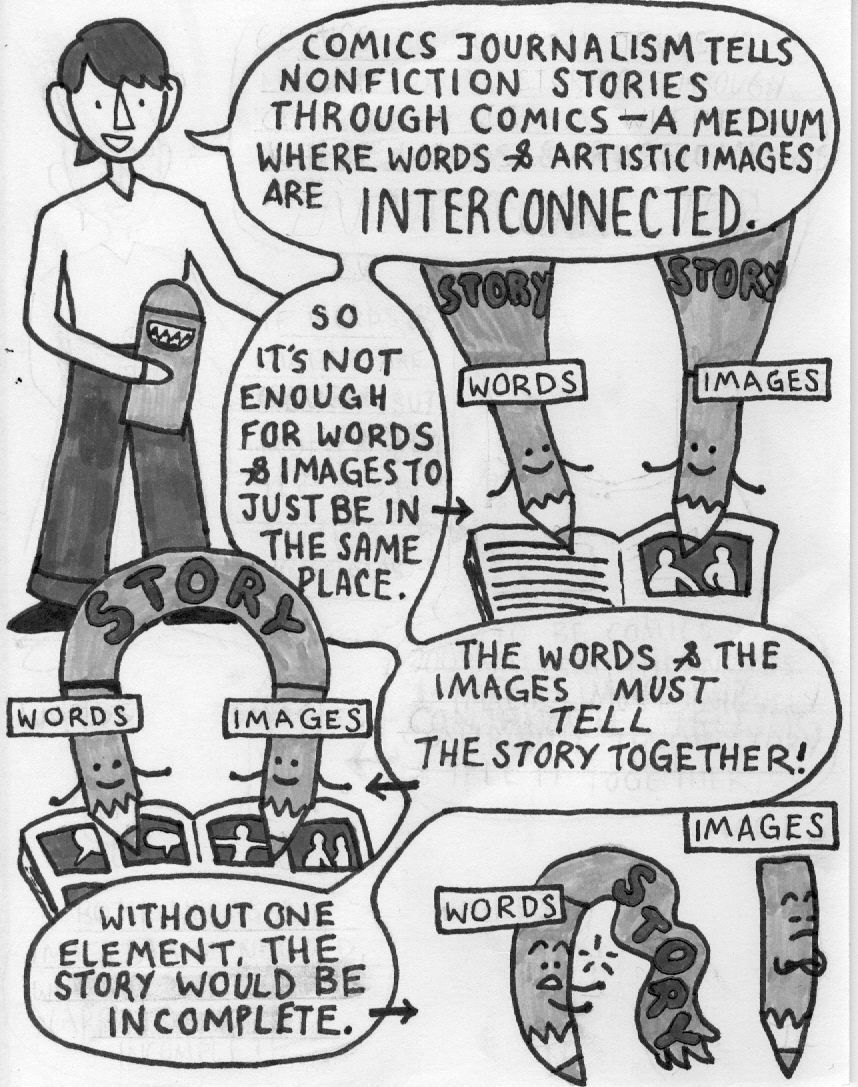

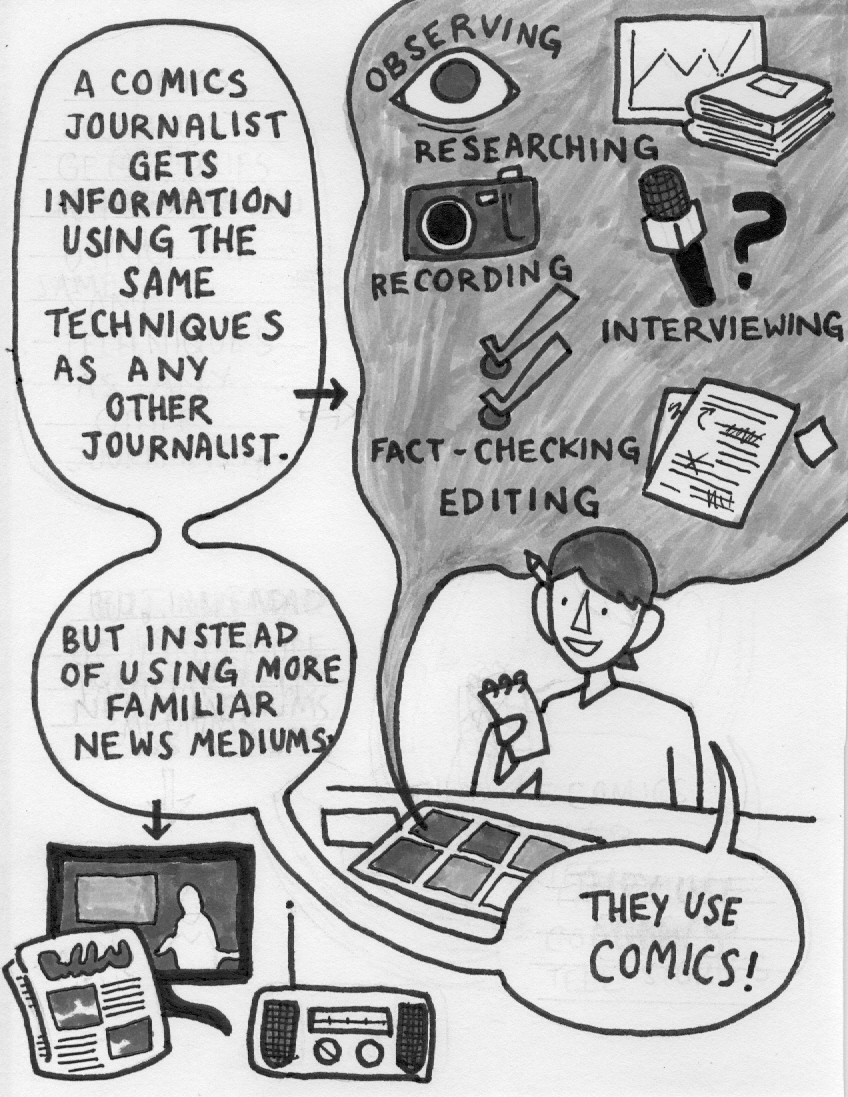

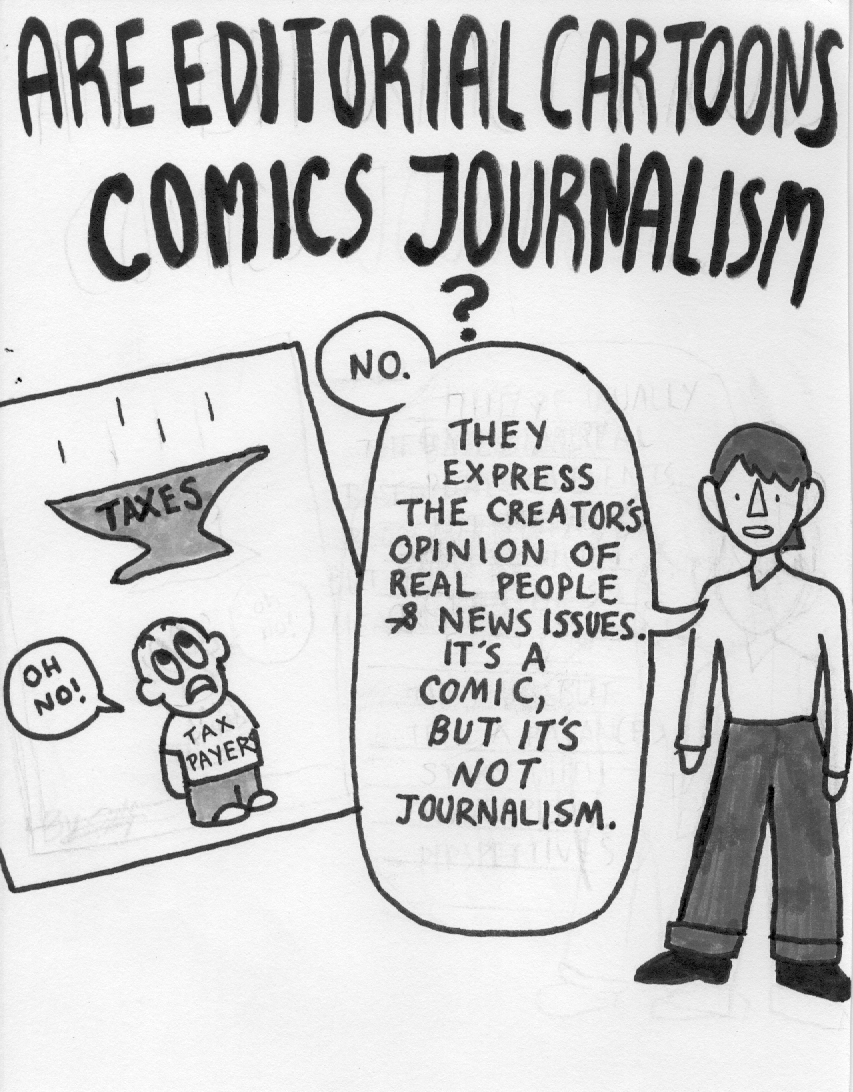

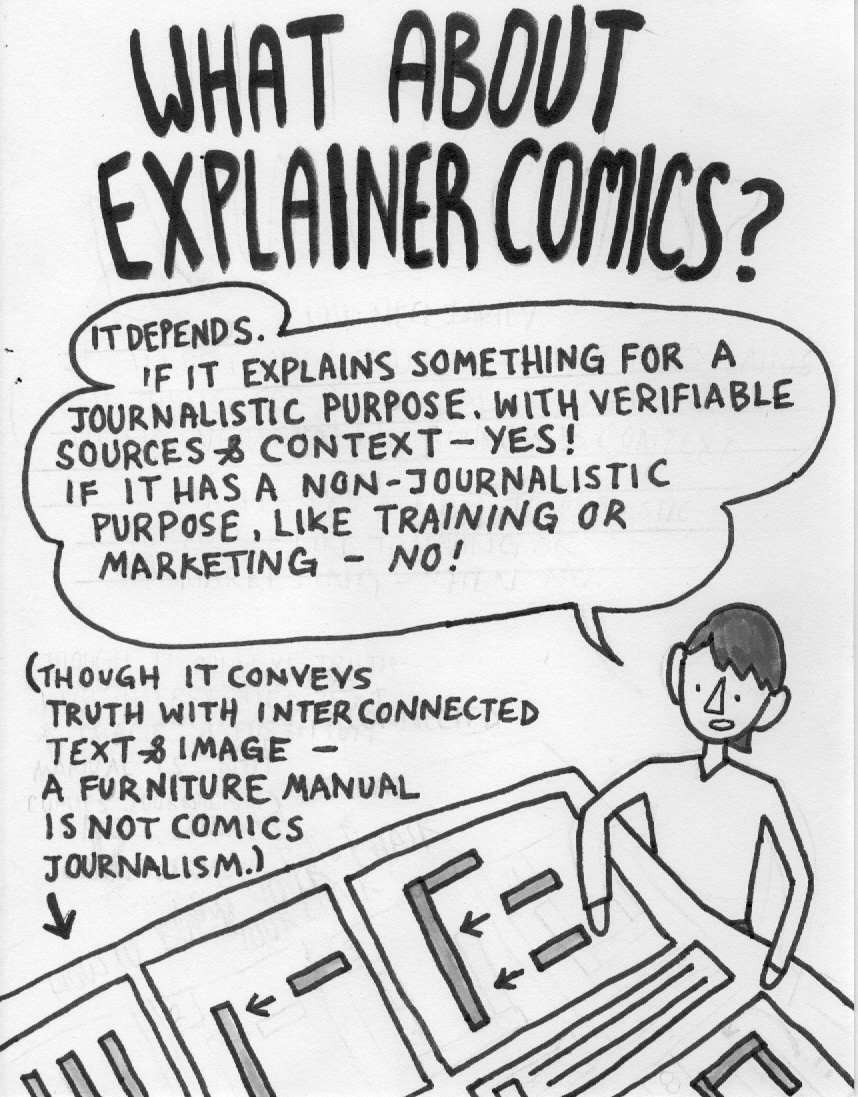

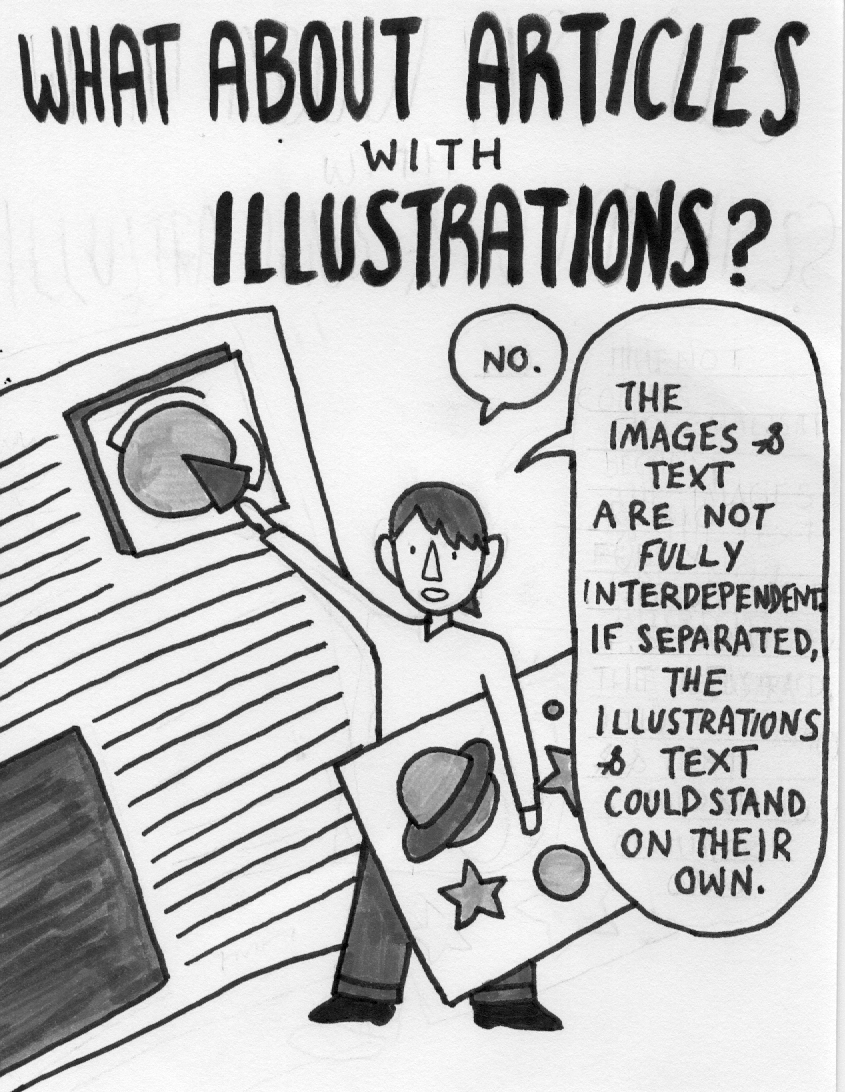

This form has many names: graphic journalism, illustrated journalism, graphic non-fiction, comics journalism. With some differences, all involve creators using words and artistic images to convey real information.

Still, many are unfamiliar with this kind of journalism.

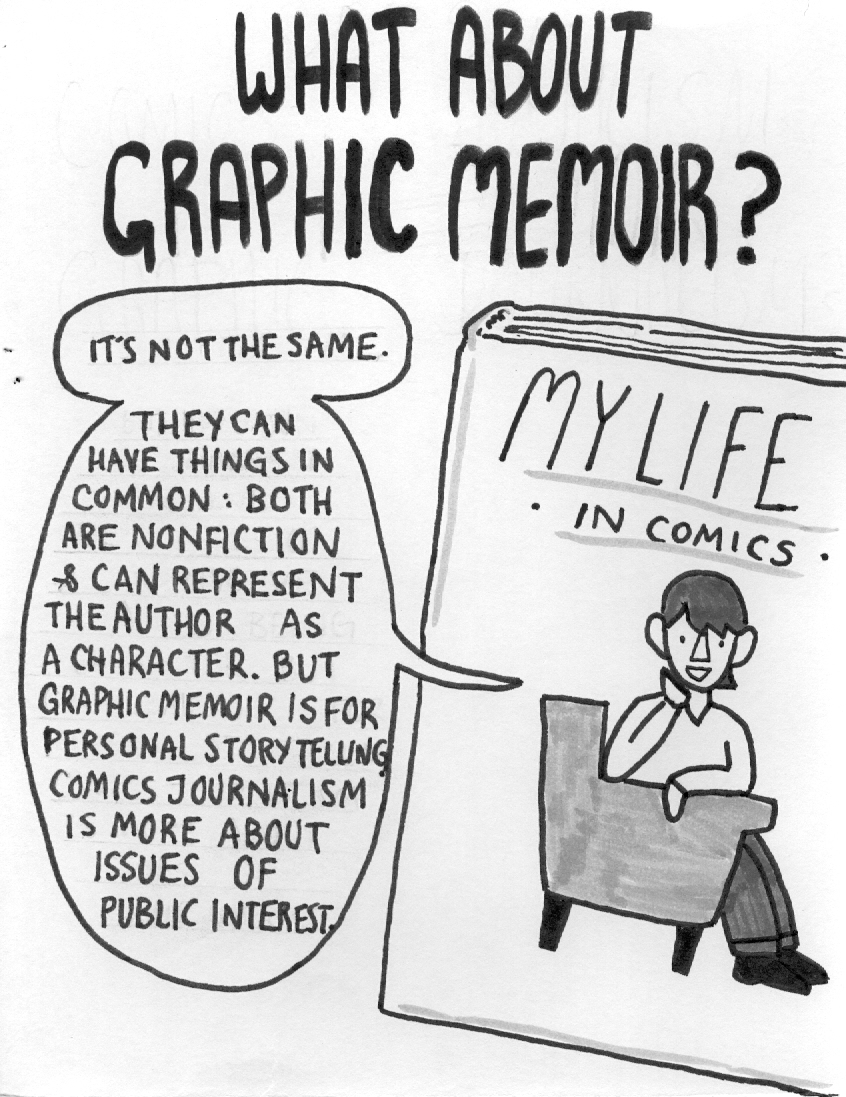

Illustrations by Wilson Henry

Comics journalism joins a media landscape tangled with the values of journalistic detachment and objectivity. Though many question these values, they still hold sway.

In a 2012 to 2015 study of journalists across 62 countries, 72 per cent felt that being a detached observer was “very” or “extremely” important. Reuters’ 2021 digital news report surveyed people from 46 countries and found 66 per cent thought news outlets should try to be neutral on every issue. In 2017, journalist Lewis Wallace was fired from American Public Media’s Marketplace for making a blog post questioning objectivity and arguing that journalists can “come from a particular perspective, and still tell the truth.”

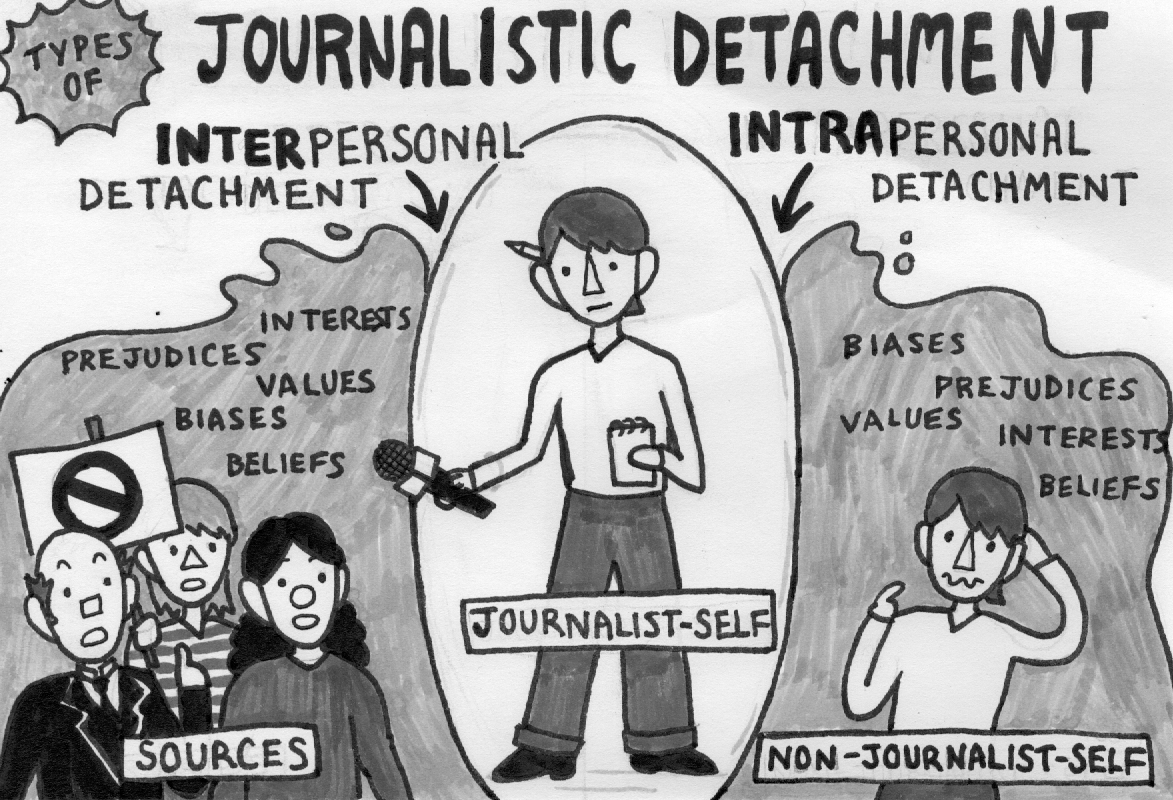

All this shows how journalism at large still values detachment, a practice that journalism ethics scholar Aaron Quinn breaks into two types: interpersonal detachment, where journalists detach from the biases and values of their sources; and intrapersonal detachment, where journalists detach from their own biases and values.

Illustration by Wilson Henry

One of the most influential comics journalists, Joe Sacco, famously foregoes the appearance of detachment by drawing himself in his non-fiction comics. Like Sacco, other creators of comics journalism are working with subjectivity, not against it, to make truthful and engaging work.

The obviousness of the human

Comics journalism’s knack for conveying truth using subjectivity could have something to do with the medium itself.

Keith Friedlander, president of the Canadian Society for the Study of Comics, says that with non-fiction comics, it’s harder for readers to forget the human behind them – and that’s a good thing.

“[Comics] make the subjective nature of reportage more obvious.”

In comparison, Friedlander says, recorded mediums like documentary film can create an illusion of objectivity.

Eleri Harris, features editor for comics journalism publication The Nib, agrees that “when something is drawn, it’s obvious that a person made that thing.”

“That kind of honesty with regard to the way that we do stories… is really valuable.”

Comics can also present subjectivity with nuance. Chantal Fraizinger, an art therapist specializing in comics art, says having pictures and words side by side creates contrast that can portray complicated emotions.

“There’s so much more… potential with [comics] when it comes to talking about emotions, because emotions themselves are so complex, and they can be so contrary.”

Cartoonist and illustrator Rebecca Roher says she uses this potential in her non-fiction comics, which have been published on The Nib and Bitch Media. When you contrast emotions like humour and sadness, she says, they can deepen each other.

“There’s something very human about that,” Roher says. “It kind of helps [the reader] connect with empathy.”

But the strength of subjectivity in comics journalism doesn’t necessarily end with the drawings.

Transparency and insight

Eleri Harris is also a cartoonist and journalist. For Harris, a personal connection to a news event helped her create a comics journalism series that explores a different angle to a widely reported murder conviction.

In 2010, Susan Neill-Fraser was convicted of murdering her husband, Bob Chappell. In 2017, Harris published seven comics about the Tasmanian murder conviction. The series came from two years of hefty research and Harris’s personal connection to the daughter of Neill-Fraser.

Harris drew herself reporting the story and greeting the main subject – her old schoolmate, Sarah Bowles. Harris did this to make her bias as the storyteller transparent.

Coming from a background in broadcast journalism, Harris knows that many journalists are taught to avoid reporting stories they are close to. But she has a different view.

“I think that being close to a story gives you insight.”

Harris’s closeness allowed her to dig into a perspective that wasn’t getting much light in the case’s extensive media coverage.

“Losing a parent, for example, to the penal system is an experience a lot of people have had, but it’s not something you see explored that frequently in traditional media,” she says.

As an editor, Harris also values contributors who work with their subjectivity.

Connections to larger issues

The Nib, founded in 2013, is one of the few organizations devoted to comics journalism and editorial cartooning. It’s pitch-based: contributors send in story ideas and editors choose from them to publish content. The Nib’s website has hundreds of contributors.

Harris says people with personal connections to their proposed stories can stand out.

Much like written news features, The Nib’s comics features explore larger themes and issues. Typically, a comics feature takes about six weeks to make, so it can’t follow the daily news cycle.

Harris says The Nib aims to get the voices of people who are typically underrepresented or neglected in mainstream media.

“Giving them an opportunity to describe their story visually, or their takes on specific issues is…valuable.”

The Nib has published comics essays from contributors who weave their personal experiences with topics like the implications of online ancestry tracing and the #MeToo movement.

Creators can also harness subjectivity to convey stories that aren’t their own.

Asking, ‘where do I fit?’

Jon Claytor doesn’t identify as a journalist. But in the past few years, he’s interviewed sources, studied photographs and done research – all to make non-fiction comics.

Most people in Claytor’s comics aren’t conventional newsmakers. Some are corner store owners or philosophy students. Some have told Claytor about what it’s like to come out at age 55, or what it’s like to move from Lebanon to Canada. His latest CBC comics series is called “Life Paths.”

Natalie Dobbin, a CBC producer and Claytor’s editor, says stories published through her branch – the creator network – aren’t hard news.

“Our goal is trying to represent how people live in all different parts of the country.”

She says Claytor’s profiles put “a face on a story in a different way.”

Claytor sees his work as a collaboration. In interviews, he says he lets sources take the lead in telling their stories. For him, the process can create an emotional connection.

“It’s a different kind of connection to be drawing somebody… I’m thinking about them and I’m thinking about how they’re feeling.”

Throughout the process, Claytor questions where his subjectivity belongs in the story.

“There is, like, this give and take. Because it’s a drawing. My lines are there, my voice is there. I can’t pretend it’s not. But I try to stay focused on that emotional connection that I have with the person.”

This isn’t a detached approach to storytelling. But it shares traits with the methods of journalists who aim for more ethical reporting.

When handling the personal stories of sources from communities that are chronically misrepresented in news, journalists in a recent ethics guide from University of Wisconsin-Madison suggest giving the source more control over how their story is told. The same guide recommends ongoing consideration of how the story and the journalist-source relationship could impact the source’s life. Another guide, from the American Press Institute, recommends empathetic listening as a tool for better reporting on media-neglected communities.

Listening to stories

Ann LaBillois was not the only person to recognize herself in the comic about her life. She remembers her youngest daughter’s reaction:

“She said, ‘Wow, you know, it’s amazing how you’ve come through all this’… those are the words that we dream of hearing from our kids.”

With his comics journalism, Claytor doesn’t aim for detachment. His goal is to encourage listening.

“I really feel that stories are the thing that can save the world. Just listening to stories.”

LaBillois also sees power in the act of listening.

“When I really listen, I know I’m in the right place. I’m meant to be here. I’m going to learn something.”

About the author

Wilson Henry

Wilson Henry is a writer and amateur comics artist based in Halifax. Their interests include visual art, horses and podcasting.